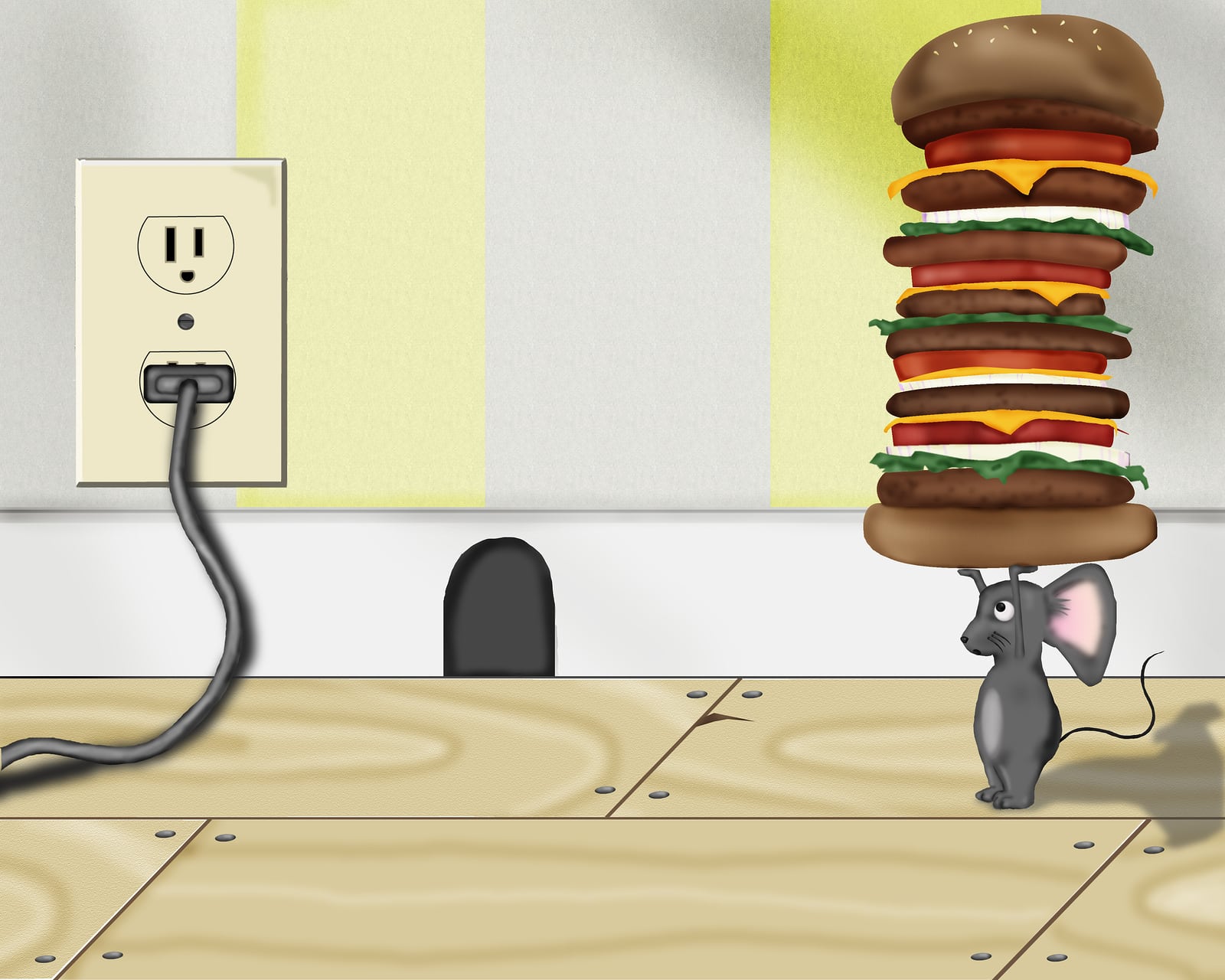

The newspaper headline was enough to get nutritionists wondering: “Fat enzyme breakthrough kept mouse thin on pizza and burgers diet”. Those of us with a questionable diet were wishfully thinking that at last here was something that meant we could eat fast foods to our heart’s delight.

The story continued: “An obesity breakthrough appears to have been made by Danish researchers who say they’ve found a way to keep weight off while eating a pizza and burgers diet. Pizza chips and burgers can be consumed without gaining weight if a certain enzyme is reduced, new research has discovered.”

Surely one of the biggest breakthroughs in food technology in years. Or was it?

Alarm bells always ring for me when a story follows up an unequivocal headline with something like “appears to have been made”. It’s usually newspaper code for “everything you’ve just read could be completely wrong”.

Sure enough, the study wasn’t about a mouse staying thin after scoffing pizza and burgers. The researchers had tested mice with the enzyme along with control mice, who became obese on the same diet that “more or less corresponds to continuously eating burgers and pizza”.

In the fullness of time the finding could prove to have merit, but it’s not based on feeding mice pizza and burgers. That didn’t stop the NZ Herald writing a headline that would mislead. It seems to be a trend in these days of “click bait.”

Sadly, these sorts of “sciencey” half-truth reports happen regularly as writers believe they have to embellish science to make it interesting.

One of my favourites over the years was a story, in the same newspaper, proclaiming “A sweet a day helps kids grow up violent”, or worse still, “letting your children eat sweets could turn them into serial killers”.

It claimed researchers had found that children who ate sweets every day were more likely to be violent as adults. It was based on a study that showed nearly three-quarters of the participants who had convictions for violence in their early 30s had eaten sweets nearly every day during childhood, compared to 42 per cent who were non-violent! Seriously? Nothing to do with poor parenting and a deprived upbringing?

This is a classic example of association research that overlooks one of the golden rules of research analysis – correlation is not causation.

It wasn’t so much the headline but that the story was run at all. It was so outlandish that it shouldn’t have been in a publication that expects consumers to take it seriously. Perhaps in the “Weird and Wacky” section but not in the Wellbeing section alongside nutrition ideas and feijoa and lemon chutney recipes.

Sometimes I feel like a broken record on issues like this, but I make no apology: consumers should expect to be reliably informed when they read such articles, not have to put up with cut-and-paste regurgitation from dubious sources disguised as helpful and chosen just because it makes a good headline.

There are plenty of reputable places the media can source accurate material.

For example, the American Council of Science and Health. It’s a non-profit advocacy organisation formed to publicly support evidence-based science and medicine. As it describes itself, “we were created to be the science alternative to ‘news’ that is often little more than hype based on exaggerated findings, and to help policymakers see past scaremongers, activist groups who have targeted GMOs, vaccines, conventional agriculture, nuclear power, natural gas, and ‘chemicals,’ while peddling health scares and fad diets”.

And they live up to that. They employ Ph.D’s and M.D’s supported by an eye-watering list of physicians and scientists who peer review their reports and participate in seminars and other educational activities.

It’s simple, honest research published without fear or favour. Their latest work includes titles such as ‘Are Breastfeeding Messages Actually Hurting Mothers?’, ‘Does Fast Food Affect Fertility?’, and ‘New Study Refutes the ‘Wine Will Kill You’ Nonsense’.

The media has a moral duty that wellbeing material they publish is accurate and research-based, and it could do a lot worse than look at what these people are doing.

(originally published in FMCG Business)